Add a little control.

Don’t assume that hard work alone can overcome everything—it’s an idealized notion. — Li Na

Imagine this

Imagine, wildly and creatively—what if we set aside our physical bodies and let the racket generate its own motion? Could it still produce spin, flat hits, powerful shots, or even slower, controlled swings?

The answer is yes, because the variety of returns depends on the angle of impact between the racket and the ball, as well as the conversion of kinetic energy.

(According to the physics definition, kinetic energy E = mv², where velocity v is a vector—possessing both magnitude and direction. The numerical value of the clubhead speed directly influences the magnitude of the kinetic energy, while the direction of the clubhead speed itself determines the angle of impact.)

The hitting motion can be understood as follows: Our body uses specific structural mechanics and muscular strength to maintain the racket’s angle while simultaneously accelerating it. For beginners, the key to mastering tennis control lies in perfecting the angle at which the ball makes contact. Meanwhile, advancing players focus on fine-tuning their ability to control the ball’s trajectory by balancing speed—this aspect of controlling the ball becomes a more sophisticated level of understanding.

Take a look.

We’ll use a high-speed camera capturing 6,000 frames per second to observe the ball-striking process.

A Hit Under High-Speed Camera

We can see that the contact between the racket and the ball happens in milliseconds—far too fast for us to make such precise, rapid adjustments with the racket. This means we simply can’t control the exact point of impact or accurately fine-tune the angle of our shot. In fact, all those mental "first this, then that, and finally something else" strategies we have in our heads are completely unattainable.

What do tennis experts do? They never gamble on odds—they simply do the right thing: keep the racket face steady and let the racquet meet the ball.

In three-dimensional space, they maintain the racket's movement over a very short distance—so short that as long as the tennis ball makes contact with the racket within this tiny interval, the angle of collision between the racket and the ball remains constant.

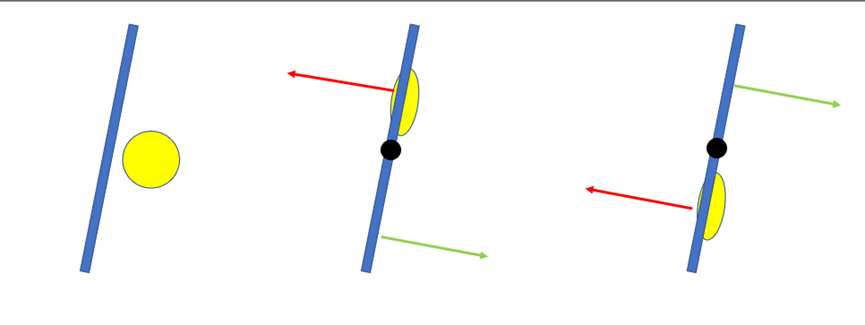

For ease of understanding, we’ll use an abstract representation: the racket’s trajectory in space forms an extremely short, irregular cylindrical shape. As long as the tennis ball touches any cross-section of this cylinder, the angle of impact will remain fixed. The red cross-section represents the racket’s position at a specific moment.

Tennis and the Collision of the Racquet Trajectory (Using a Flat Hit as an Example)

This clearly shows that a player's ability to maintain racket face movement across various techniques directly determines their control over the ball. The smooth, forward-directed motion during the hitting process is what we commonly refer to as "pushing forward."

Let's think it through.

Can the commonly referred-to "package ball" and "eating the ball" really be understood through the lens of control? The author would like to explain this by considering two distinct scenarios.

First,If you imagine wrapping the ball like you would a Christmas apple, keeping the ball stationary while the racket’s face changes and rolls across the surface, that’s actually a misconception.

Blue represents the racket, and yellow represents the tennis ball.

(The illustration shows the racket rolling over the ball.)

In this case, it’s a major misconception to assume that changes in the racket face automatically create spin—please correct this misunderstanding as soon as possible. Not only does it affect the quality of your shot, but in severe instances, it can even strain your wrist. Tennis spin actually results from the relative motion between the ball and the racket; relying solely on friction between the two is nowhere near enough to generate significant spin. Instead, spin occurs when the tennis ball compresses and deforms upon hitting the racket surface, then rolls along the strings for a short distance. The longer the ball rolls across the strings, the faster the spin becomes.

The farther the distance rolled, the faster the rotation.

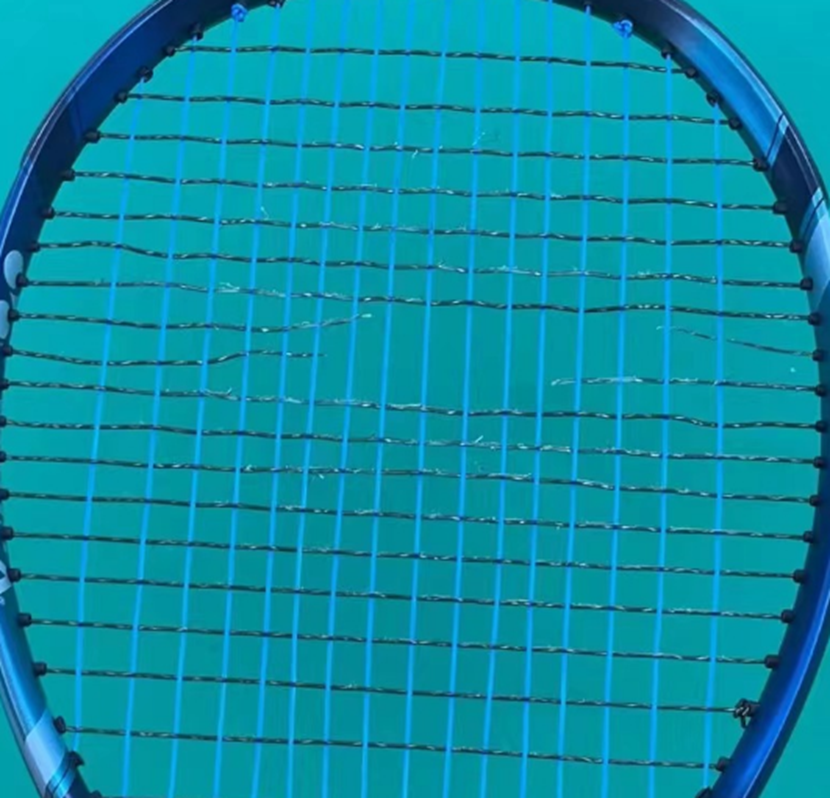

We can examine the strings of the racket: if there are many burrs, it indicates that the player tends to generate more spin during play. Conversely, if there are fewer burrs—suggesting the strings break primarily due to sheer pulling force—it means the player relies more on flat hitting. Importantly, both flat and spin-based techniques don’t necessarily affect a player’s ability to maintain control. The perception that topspin shots offer better control stems from aerodynamic observations, where the airflow generates downward pressure on the ball, making it less likely to drift out of bounds. From the perspective of the hitting surface, as long as the player can keep the racket face steady and under control while moving, they’re demonstrating solid shot placement and precision.

Second,If you consider the "package ball" an abstraction, that’s perfectly acceptable—but how exactly this abstraction is defined qualitatively and quantitatively remains a question worth discussing.

The author believes that, when explained from a rational perspective, the "wrap-around effect" is more accurately described as the ball exerting a force on the racket. To maintain the racket's angle, the player holding the racket applies a certain amount of force to counteract the twisting motion—this force is both qualitatively perceptible and quantitatively measurable using scientific methods.

The diagram below illustrates, at the moment of impact during a forehand stroke, the force exerted by the tennis ball on the racket (shown as a red arrow), as well as the force applied by the player’s hand to maintain the racket face angle (shown as a green arrow).

Correction: The direction of the green arrow in this image is incorrect—it should point in the opposite direction.

Once the stable racket face applies an anti-torque force during the forward push, we can say, "the ball is well 'eaten'—meaning the racket has excellent control and wraps securely around the ball."

Observe again

Now, let’s switch back to the high-speed camera capturing 6,000 frames per second. Taking a forehand stroke as an example, here’s what happens at and around the moment of ball contact—step by step.

Maintain the racket face angle and push the ball a short distance.

We observed that before and after the swing, players made a conscious effort to maintain the racket face. Interestingly, immediately after impact, the racket face didn’t change right away—but instead, it continued moving forward for a brief distance before the forearm began an inward rotation, at which point the racket face angle finally adjusted.

So can we understand that professional players never gamble on probabilities—but instead do the right thing?

Whether it’s serving, forehand or backhand strokes, or volleys, use a steady racket face movement to track the ball’s trajectory over a short distance.

For beginners, the racket face angle is all about control!

There's no need to sacrifice ball control in pursuit of head speed!