How to Gradually Improve Your Tennis Anticipation Skills? (Conceptual Approach)

01

Writing Context

In the field of tennis coaching, there’s always been a major challenge—anticipation.

The reason it's difficult to teach is that some coaches rely too heavily on experiential methods—failing to scientifically assess players' predictive abilities and neglecting a gradual, step-by-step approach to skill development.

The reason it’s difficult to learn is that some students mistakenly believe this skill feels more like a "personal experience"—an experience that seems intuitive yet elusive, making it even harder to master.

This article, serving as the conceptual section, aims to clarify two key points:

1. Anticipation is a skill that can be assessed and improved upon;

2. "Understanding and anticipating how to execute the spin" is at the heart of manifesting capability.

In beginner-level net-cord feeding drills, coaches often confuse two issues: "weak anticipation skills" and "distracted attention." Players with poor anticipation tend to appear visibly confused during training, leading some coaches to mistakenly attribute this behavior to a lack of focus—despite the fact that these students are already drenched in sweat from being overly concentrated!

This situation is like day not understanding the darkness of night—students feel wronged, while coaches struggle. If players show sluggish movements during net-based training, the author believes that clarifying the issues mentioned above is the key to breaking the current stalemate between both the "teacher" and "learner." Otherwise, they’ll inevitably end up stuck in the rut of simply "focusing intently on the ball."

02

Levels of predictive ability

As a skill, predictive ability follows the same developmental principles as other competencies—progressing gradually from basic to advanced levels, with each step building upon the last. The author divides this ability into two progressive stages based on difficulty: beginner and advanced. It’s important to note that skill development inherently involves distinct, non-overlapping stages; lacking a solid foundation at the initial level will directly hinder the acquisition of more complex, advanced skills. For instance, one must first develop an awareness of creative spatial possibilities before being able to execute rotational movements in response to the ball’s trajectory.

Beginner's guide to "dodging" — creating space for your shot.

For tennis beginners, the "in-front-of-you shots" are just as challenging to handle as the "out-of-reach off-the-ground shots." While hitting an in-front-of-you shot doesn’t require extensive, wide-ranging movement like an off-the-ground shot does, why does it still prove tricky for beginners to anticipate?

A player’s most fundamental predictive ability is simply to avoid the ball—yes, you heard right, it’s all about “dodging.” As tennis is a “swing-based sport”—where the farther away the hitting point, the greater the power that can be generated—players must actively create space for their swing.

The academic community often uses the "double pendulum experiment" to model swing-type movements.

The second pendulum requires sufficient space to accelerate.

"The ability to anticipate a 'dodge' is instinctive—much like the childhood game of dodgeball, where all we have to do is read the trajectory of the ball: jump up, crouch down, move left, or step back right. Unlike dodgeball, though, tennis hitting technique relies more on players’ anticipation of lateral movements; adjustments in the vertical direction typically come only in unusual situations. As a result, tennis seems "easier to predict" than dodgeball—at least on the surface."

Unfortunately, beginners often find themselves standing too close to the ball's trajectory after picking up their racquet, which compresses their hitting space—and in more serious cases, even leads to being hit by the ball on their body or face. This isn’t because they’ve lost their ability to anticipate "dodging," but rather because they fail to mentally activate the awareness of "creating space" for their shot.

Moving laterally to guide the tennis ball’s flight path past either side of your body is the most fundamental form of anticipation. In net-play practice, it takes real courage for beginners to persist in training their left-right anticipation—with a healthy dose of respect for the sport. On the other hand, if they rush into aggressive plays impulsively during drills, losing their sense of direction in the process, they’ll end up paying a much higher price—especially male players.

When developing basic left-right anticipation skills, don’t be too hard on players if they fail to make contact because they’ve anticipated too far—after all, a single accurate anticipation is far more valuable than a (reluctantly) blocked return. After all, the player is actively moving to create the ideal space for their next shot.

Advanced "Aim" — Anticipate and fully rotate your body afterward.

After players develop their ability to anticipate the ball's movement in the left-right, two-dimensional plane, coaches should help them extend this predictive skill into the full three-dimensional space.

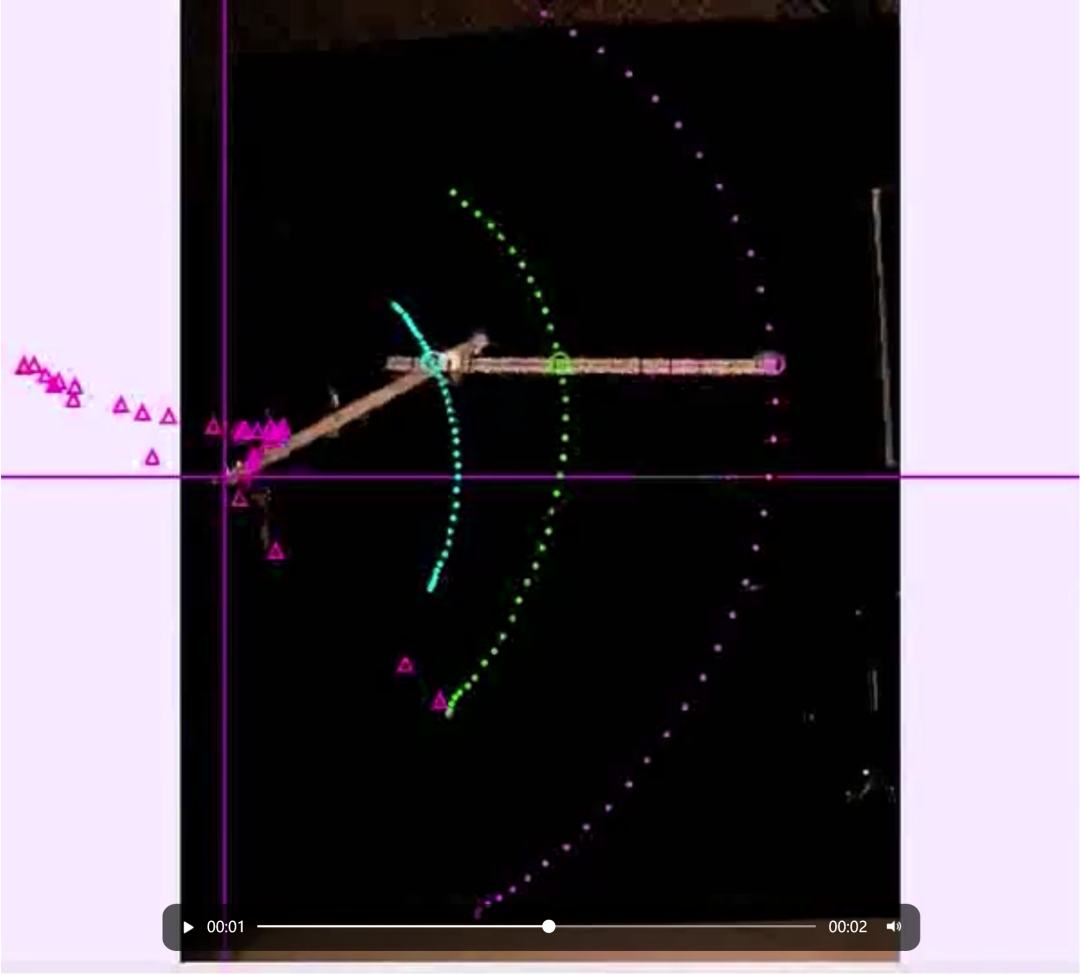

Ideally, the ball’s flight and bounce follow a trajectory lying in a single plane. After the opponent’s racket makes contact with the ball, players should promptly align their pelvis parallel to this trajectory plane by shifting their body position and rotating their torso. The author refers to this predictive ability as "aiming."

Assume the ball's trajectory lies on a single plane.

The key to anticipation lies in quickly rotating your body—keeping your pelvis parallel to the plane of motion.

To better understand how to "aim" with the pelvis, let the author draw on forehand hitting technique to help players clarify the relationship between "advanced anticipation" and the "hitting frame."

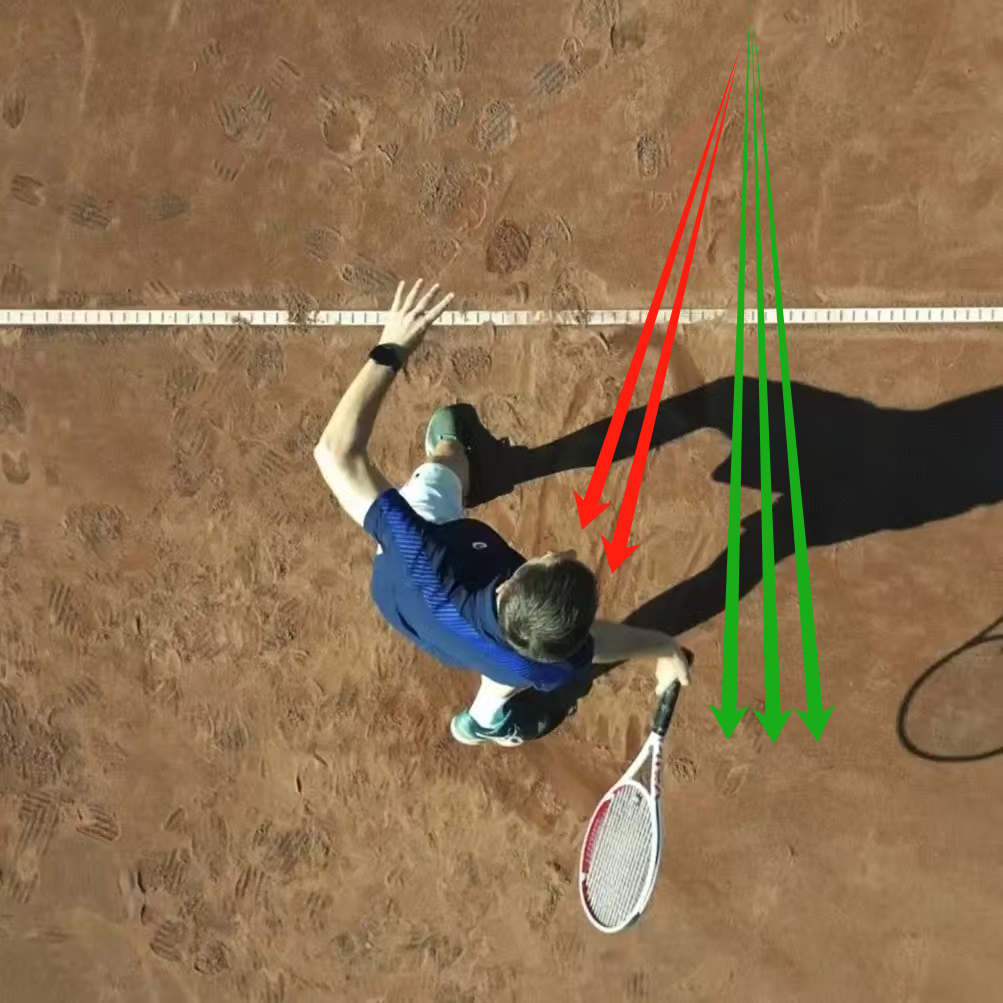

A well-structured forehand stroke, when viewed from above, shows that the movement patterns of the wrist and racket head closely resemble those observed in a double pendulum experiment—both exhibit a characteristic "nearly circular arc." Sometimes, we describe a player’s motion as either "tight" or "loose," which typically indicates that the wrist and racket head are moving with excessive inward rotation or outward twisting, respectively.

A well-structured forehand stroke from a top-down perspective

The motion trajectories of the wrist and racket head exhibit a "nearly circular arc" characteristic.

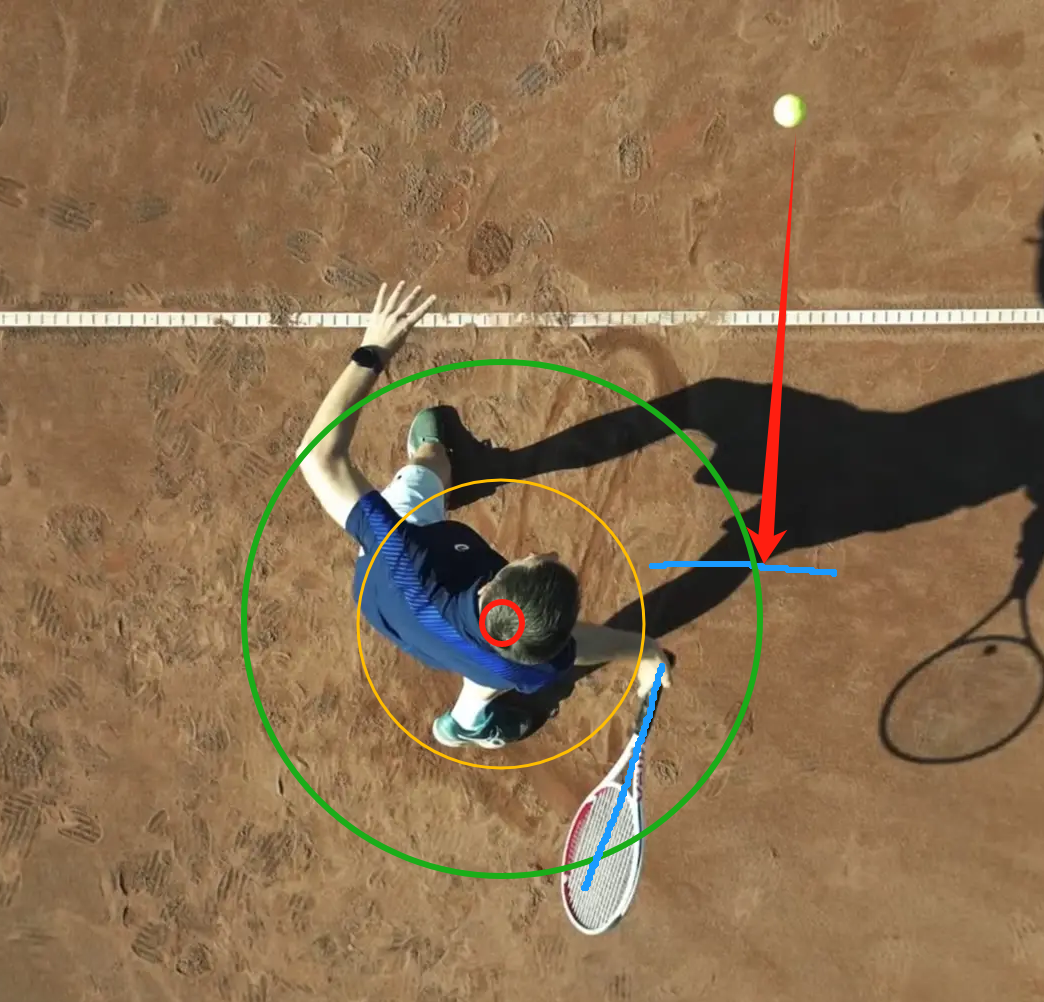

When a player strikes the ball at the baseline, only by positioning the pelvis beforehand in a fully loaded position—parallel to the swing plane—is it possible to regulate the racket-head speed through the rotational power of the hips, rather than relying on arm strength. This is the key to achieving stability and consistency in tennis shots.

Loading position

Experience shows that in the loading position, keeping the pelvis parallel to the tennis ball's trajectory allows players to maximize rotational power while maintaining a stable hitting frame throughout the swing.

Fully rotate into the loading position,

The pelvis is parallel to the swing plane, ensuring a stable hitting frame.

When the pelvic angle is too large relative to the front side of the tennis trajectory, it can easily lead to overextension of the body during the swing and a late impact point.

Insufficient rotation in the loading position,

The pelvic angle relative to the swing plane is too steep, resulting in a late impact point.

When the pelvic angle is too small relative to the front side of the tennis trajectory, it can lead to insufficient rotational movement during the swing, causing the hands to cross prematurely and hitting the ball at an earlier-than-ideal point.

Over-rotation during the loading position,

The angle between the pelvis and the swing plane is too small, resulting in an early impact point.

The issue of the angle between the pelvis and the tennis trajectory plane has been resolved—so how do we control the distance between the pelvis and the trajectory plane? The answer is simple: extend your non-dominant hand—the non-racket hand serves as a crucial reference point for gauging how close or far your body is from the tennis trajectory plane.

Use your non-racket hand as a reference for measuring distance.

Once you've mastered the distance, strike decisively.

Anyway, advanced anticipation should first focus on improving the angle issue—ensuring a solid hitting frame—before addressing the distance-related flaws—integrating anticipation into your overall movement system.

03

To conclude

The core idea of this article is to systematically explain the two key tennis anticipation concepts: "creating hitting space" and "fully rotating your body after anticipating."

Although the author has thoroughly deconstructed the pathway for developing predictive ability through a progressive training framework, space constraints prevented an exhaustive exploration of various technical details and advanced training techniques.

May readers thus sow the seeds of technological awareness, nurturing them through consistent practice until they take root, blossom, and ultimately evolve into a strong, dedicated habit.

🙏 If you found this article helpful, please follow the author—(the training series) is being rapidly developed. 🙏