Who has the stronger propulsion in freestyle—shoulder-driven or hip-driven? Don’t forget to maintain your core stability during either technique.

When turning your body to the side, your shoulders and hips should move in sync, though their range of motion doesn’t have to match exactly. As a beginner, if your core isn’t engaged tightly enough—simply put, if you’re not drawing your belly button toward your spine and cinching your waist—the shoulder-to-hip rotation may become uneven. And when there’s an inconsistency between how much your shoulders and hips rotate, it typically indicates twisting at the waist. If your core lacks sufficient strength during this twist, your body is likely to feel unstable and loose, leading to disjointed movements like inconsistent arm strokes and flutter kicks—preventing you from generating unified, powerful propulsion through the water.

Therefore, whether the shoulders and hips maintain a consistent range of lateral rotation should be determined based on your core strength. If your core is stronger, you can afford a greater difference in the amplitude of shoulder and hip rotation—meaning you can twist your waist more significantly without compromising your body’s alignment. Conversely, if your core is weaker, it’s best to keep the shoulder-to-hip rotation as minimal as possible, preventing excessive waist twisting that might otherwise make it difficult to maintain proper posture.

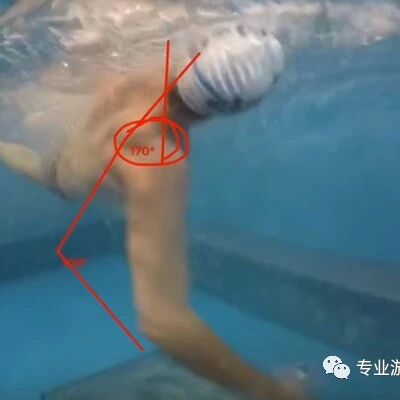

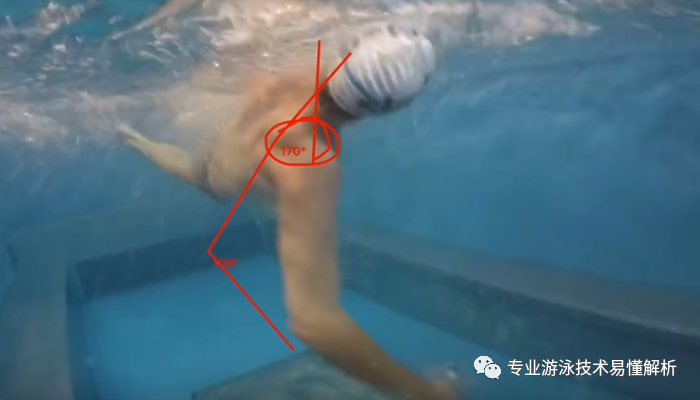

The maximum range of shoulder rotation should be limited by ensuring the elbow does not extend past the back. In other words, shoulder rotation is designed to allow the elbow to naturally and comfortably push the water backward. Importantly, during this motion, the elbow must never cross over the back. If you feel tension or strain in the shoulder joint or upper back while pushing the water, it’s a sign that either your elbow is positioned too far back—or that your shoulder rotation isn’t sufficient.

The maximum hip rotation should be limited to the point where the hips don’t lose contact with the body due to gravity. This might sound tricky to grasp—just imagine performing a plank, leaning your body sideways. If you tilt too far, your hips will no longer have support underneath, making it incredibly difficult to return to your original position. At that point, you’ll either end up rolling completely onto your side or simply collapsing forward at the waist. Similarly, in swimming, excessive hip rotation can lead to one of two problems: either it becomes painfully challenging to initiate the next turn toward the opposite side, or your lower back starts to feel unstable during the movement. As a result, your upper and lower body can no longer stay aligned and rigid as a single unit. Even if your core strength is strong enough to maintain that rigidity temporarily, it’ll still disrupt your swimming rhythm—and worse, it could waste valuable energy by directing effort into unnecessary movements rather than propelling you forward efficiently.

Related Articles

There are too many misconceptions about the full immersion technique—specifically, the importance of the second kick and the arm entry into the water.

Freestyle swimming becomes more tiring the longer you swim, and here are three common reasons why.