Skiing Diary: Another Beginner Snowboarding Session in Early 2025

A few weeks ago, Young, the friend who skis and teaches at the highest level around me, accepted my invitation to come back to Canada—to ski with me again and even give me some expert guidance along the way.

Since I’m getting older and becoming even lazier, this time I’ve focused more on entertainment and kept the teaching aspects to a minimum. Still, I’ve managed to gain quite a bit of insight into skiing—so whenever I have a moment, I quickly revisit my notes to reinforce my understanding and share them with fellow ski enthusiasts.

Before hitting the snow, I thought I had only two main issues: carbines and A-legs.

Carbine glide

I clearly realize that what I used to call "carving" was actually just a result of picking up speed, with edges engaging sharply on the outer edge of the turn to create a defined path—but neither during the entry nor the exit of the turn did I actually carve. Instead, I relied on snow-scrubbing techniques, so it wasn’t true, full-fledged carving at all, and certainly didn’t leave any clear, crisp ski tracks in the snow.

First, identify the issue: I tend to rush into edging right before turning, quickly rotating and kicking the board out to initiate the edge. As a result, the board never properly engages the edge from the start, and when exiting the turn, it also fails to maintain that edge—instead flattening out and missing the crucial process of re-engaging the edge. This leads to a pattern of carving turns that involve spinning and rubbing the snow rather than smooth, controlled carving. Once you understand the root cause of this problem, the key is to consciously focus on maintaining and feeling the edge—both as you exit and enter the turn—and to fully engage in the process of establishing a new edge.

Motion trajectory

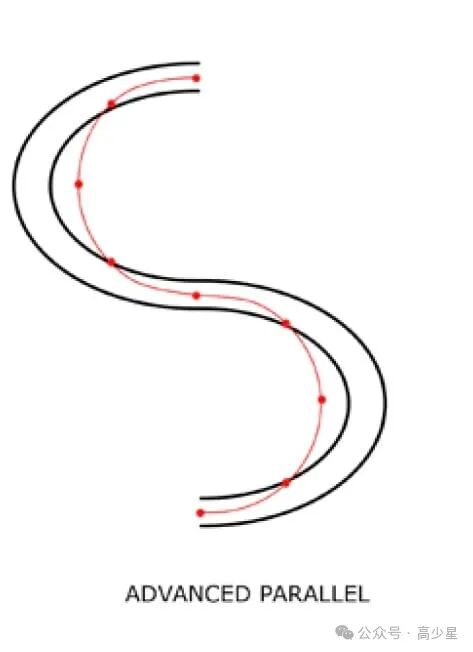

After explaining how to carve and filming a run for me, Young shared with me the most crucial concept of skiing—and that’s exactly what I need to work on improving the most, as shown in the image below.

Anyone who’s ever learned to ski has probably seen this image—doesn’t it just look like the parallel turn? At first, I was a bit dismissive of it myself, until Young broke down every tiny detail for me: from the skis themselves to your legs, ankles, and even your entire body. He explained how your body shifts—not just side to side, but also up and down—and painted a vivid, multi-dimensional picture of the entire movement. Only then did I finally gain a relatively clear yet comprehensive understanding of skiing, finally grasping how all the pieces fit together to create that seamless, flawless glide. And that’s precisely what makes skiing so fascinating in the first place.

I doubt I’ll fully grasp this diagram even in two or three years. For now, all I need to remember is that the red line represents the movement of my body’s center of gravity—it doesn’t and shouldn’t align with the black line tracing the snowboard’s path. Instead, as I carve through turns, my body continuously moves forward, cutting across the board’s trajectory. In practice, I used to feel like my body was simply following the snowboard; now, though, my body naturally leans downhill while allowing the board to stay on the outside, smoothly tracking its movements as I initiate and complete each turn.

The video below isn’t about me already nailing it—how could I possibly do that when I’m just starting to understand? But there’s definitely been a little improvement. You might spot other issues in the video, but at the time, my main focus was on feeling and practicing this particular movement pattern.

Inner Leg Management

Next up is the visibly noticeable "A-leg" issue—a problem that’s both complex and straightforward. On one hand, an A-leg forms because certain leg muscles remain underused due to an individual’s innate physical structure combined with prolonged, habitual sitting. As a result, this issue has little to do with a person’s sliding experience or skill level; for instance, some beginners never develop an A-leg at all, while even seasoned skiers often struggle to correct it. On the other hand, at its core, overcoming this challenge simply requires shifting your focus: instead of concentrating solely on your outer leg during turns, consciously engage your inner leg as well. By practicing this mindset—even starting to move your inner leg mentally before initiating the turn—you can gradually improve and master this technique.

Two-arm posture

Equally affecting the overall look are my shoulders. A long time ago, my arms were held very close to my body, making me appear somewhat feminine. Later, I consciously started keeping my arms slightly wider apart, which improved the appearance. But after shooting this video, I noticed that even though my arms are open, the angle at which they’re positioned still involves slightly bent elbows—so I’ll need to extend them farther outward for a more balanced and masculine stance.

Mushroom trim

Every day at the ski resort, I try my hand at mogul skiing. Although I can manage it, it’s pretty tiring—and when the moguls get too close together, I’m completely stumped. Young pointed out that my usual technique involves scooping straight down from the very top of each mogul, which is both exhausting and tricky to control. Instead, he suggested I switch to sliding along the edge of the moguls, slowing down as I approach the next peak and then smoothly turning around it.

At first, I was hesitant—those mushrooms were steep and huge, and I figured if I slid down them, I’d definitely lose control and end up flying right off. After a minute of inner struggle, I finally took the plunge and gave it a try. Surprisingly, I managed to stop safely. That turned out to be another one of my big takeaways.

Then Young asked me to practice the sliding technique mentioned earlier while riding on the mushroom-shaped slope, because simply staying close to the edge isn’t enough—after turning, the snowboard tends to pull you sideways, making it difficult to initiate the next turn. That’s why your body should always face downhill, letting gravity naturally pull you downward, while your legs follow the motion shown in the diagram, gliding along the edge of the mushroom-shaped feature.

Maintain the arch

Then Young told me my reverse lean wasn’t strong enough, which meant the board would drift sideways after the turn instead of allowing me to quickly pivot into the next one. I’d always thought I was consistently facing downhill with a proper reverse lean—but after watching the video, I realized that wasn’t the case at all. Guess there’s nothing left to say except: practice more!

When discussing ski trajectories, we actually practiced the "hockey stop" specifically. Even though I’ve been a Level 1 ski instructor in New Zealand for years, I had absolutely no idea what this technique was really meant to train. To be honest, even now I’m still not entirely sure—my brain just doesn’t seem wired to pick up information that way. All I vaguely recall is that it helps the body develop an arched posture and maintain a strong edge angle, both of which are crucial for smooth gliding as well as executing the "mogul" turn. But here’s the key point: the hockey stop isn’t about deliberately coming to a halt or drastically slowing down while skiing—it’s about finding that arched position and maintaining that sharp edge feel as you smoothly transition into a turn. Only then do you release your weight to flow into the next turn. And on steeper slopes, it’s especially important not to hold onto that edge until the very end of the turn; instead, you need to establish and release the edge much earlier. This approach allows you to retain full control over your speed—much like how you’d handle a mogul turn, too.

Core strength

When studying my mushroom technique, Young pointed out another critical issue: my core strength was completely disengaged. This lack of activation caused even the slightest bump to throw off my otherwise stable upper and lower body connection—though it wasn’t a true separation—but made it incredibly difficult to maintain control over my gliding and turning.

This problem stems from my past skiing habits: I’ve been too relaxed, too lazy, and unwilling to engage fully during turns. Over time, this has left my core muscles virtually unchecked and weak. But here’s the good news—by watching comparison videos, I can clearly see how others master non-edge-pressure techniques: their entire upper body and hips stay locked in perfect alignment, almost as if glued together. In contrast, I often find myself swaying uncontrollably, losing precise control over my snowboard.

Just like managing my inside leg, mastering core engagement requires me to consciously bring that muscular power into my skiing at every moment—no exceptions. Only by making this an automatic, habitual part of my technique can I finally build lasting muscle memory and significantly improve both my overall performance and stability on the slopes.

Straight-line sliding experience

After spending over ten days at the ski resort, we booked two days of helicopter skiing. On the first day of heli-skiing, I fell so hard it made me question everything—I wondered what exactly I’d been learning over the past few weeks! It wasn’t until the next day, when I switched to a different pair of skis and reminded myself to engage my core more, that I finally started to feel like I was actually skiing straight again. Turns out, when I checked, it had been six whole years since my last time heli-skiing—no wonder I’d lost my touch!

For me, I’ve had just two experiences with straight skiing so far. First, you need a long snowboard—since I’m 177 cm tall, I usually use one around 172 cm on the slopes. But for straight skiing, I definitely require something closer to 185 cm (though on day one, I ended up using a 175 cm board). Also, the binding setting has to be at least 11—not the 7.5 I initially tried. As a result, choosing the wrong board led to constant edge catches and board slips. Second, it’s all about fully engaging your core muscles. Given the challenging snow conditions, if you can’t keep your upper body stable, a fall is practically guaranteed—within seconds, really.

Summary

We went into plenty of details, but here are the most important ones to remember: movement patterns, core strength, arching, and the mushroom route selection.

Acknowledgments

Finally, I’d like to thank my friend Young for traveling all the way from afar to join me in Canada for skiing—and even for giving me expert guidance. To be honest, he shared so much advice, but unfortunately, I only managed to remember very, very little, and I’m sure there were quite a few mistakes mixed in there too. Still, no matter what, I walked away with immense value, and it reignited my passion and enthusiasm to keep pushing myself on the slopes!

It’s a pity that he filmed me in a video, but I didn’t even give him a little show of my own. How about sharing one of his awesome skiing videos from a few years ago? Thanks!

![[2014 Tour Leader Recruitment Notice]](https://api.zsiga.xyz/mp-weixin-attachment/cover/19/202128409_1.jpg)