Wrist Structure and the Batting Motion

In tennis, the wrist is the largest joint closest to the racquet; a thorough understanding of its structure can lead to improved athletic performance and help reduce the risk of sports injuries.

Principle

The axes of dorsiflexion and plantarflexion

The anatomical structure of the wrist joint determines its fundamental biomechanics.

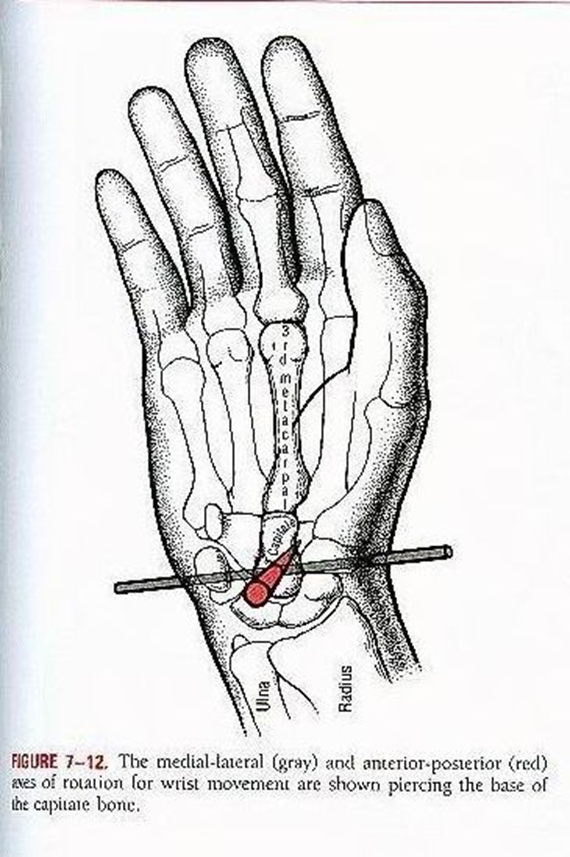

The wrist joint has two degrees of freedom: flexion/extension and rotation.

During a tennis stroke, the wrist joint primarily performs dorsiflexion and flexion movements—rotations around the axis shown in the diagram. However, leveraging this rotational degree of freedom carries a high risk of wrist injury.

Dorsiflexion of the wrist joint

When performing a full-range extension, the ligaments and muscles are stretched, and the tension in these structures helps stabilize the wrist joint, making it ideal for both forehand and backhand strokes as well as volleys.

Wrist joint flexion

The wrist joint has poor stability when flexed and is not suitable for bearing weight.

We can try pressing the back of our right hand with our left hand—first in the extended position, then in the flexed position—and we’ll notice that the extended position can handle much more pressure, while the flexed position feels intensely uncomfortable under pressure.

(I even thought about the unarmed defense technique known as the "Goose-Head Grab," where excessive flexion can cause intense discomfort.)

Practice

The moment of impact

At the moment of impact, the racket endures significant pressure. Before contact with the ball, the wrist remains somewhere between a straight position and full extension. Thanks to the stable structure provided by this extended wrist position, after hitting the ball, the wrist may slightly bend backward, creating that characteristic "hitting through" or "topping" sensation. This ensures a unified, crisp ball feel while maintaining structural integrity—allowing the racket face to continue moving forward without the wrist undergoing extensive rotational motion.

(Relying solely on gripping the handle to maintain control of the racket is a terrifying idea—first, you may not even be able to hold it steadily; second, it’s incredibly easy to develop blisters; and third, if you sweat heavily, you’ll lose your grip altogether. The more you struggle to keep hold, the more you’ll instinctively tighten up, leading to unnecessary tension in your body.)

Full flexion, straight position, full extension

Before making contact with the ball, if the wrist is positioned between a straight and a flexed state, stability is lost. The wrist must move past this intermediate position before performing the extension motion, leading to a blurred sense of touch and significantly increasing the tendency to involuntarily engage the wrist in a flexing motion—resisting the ball’s forward momentum. ("Using force to strike an object and set it in motion" is an instinctive, subconscious human response.)

So the best state is to stay relaxed—before hitting the ball, keep your wrist somewhere between a straight position and full extension. Of course, if you can achieve "head lag," you’ll actually feel that moment when your wrist fully extends.

Extended Thinking

How to identify the "wrist flick" in your swing—notice the wrist bending as it generates power.

"Whipping the wrist"—after completing the swing, your palm faces toward you, with the wrist joint bent. At this point, there’s no stable structural support holding the racket in place, which neatly explains why "whipping the wrist" often leads to a loss of control over the racquet.